Communism, a political and economic ideology advocating for a classless system where all property and resources are communally owned, has been a subject of intense debate and conflict since its inception. Its spread during the 20th century was perceived by many, particularly in the West, as akin to the propagation of a contagious disease, necessitating rigorous containment strategies to prevent its diffusion. This perception likened the ideology to toxic waste, something so potentially harmful that it must not only be contained but also isolated and buried, marked ominously for future generations to recognize its danger.

The containment strategy emerged prominently as a cornerstone of U.S. foreign policy during the Cold War, an era defined by geopolitical tension between the Soviet Union and the United States, each leading a bloc of nations ideologically and politically opposed to the other. This strategy was essentially designed to prevent the spread of communism across the globe, much like quarantining a contagious disease to prevent an epidemic. The analogy underscores the depth of anxiety that communism inspired, seen not just as a political threat but as a pervasive and corrupting plague that could destabilize societies and erode the foundations of democratic states.

To understand the containment strategy, it is crucial to delve into the nature of the perceived threat. Communism, in its ideological purity, proposed to overturn the capitalist systems of the West, abolish private property, and eliminate class structures, ideals that were inherently threatening to the capitalist and democratic norms of the Western bloc. The fear was that if one nation fell to communism, neighboring states would follow, toppling like dominoes, a theory that became a key rationale for U.S. involvement in wars in Korea and Vietnam and in various other military and covert interventions around the world.

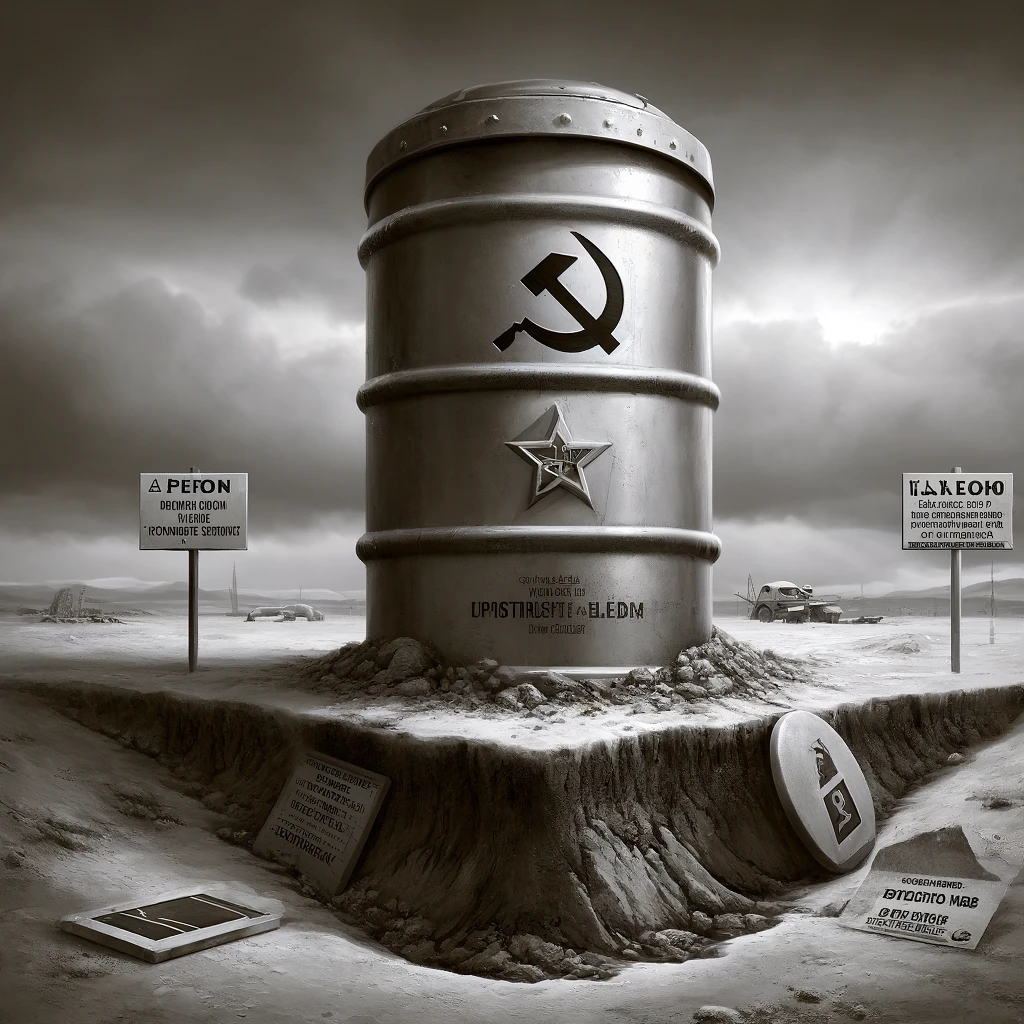

This approach to dealing with communism was similar to handling toxic waste — it was something to be sealed off, contained in a metaphorical barrel, and buried underground, out of reach and out of sight. The policy aimed not only at containment but also at ensuring that communism, once contained, would not resurface to pose a future threat. The legacy of this policy was a world sharply divided along ideological lines, with numerous nations caught in the crossfire of superpower rivalry, bearing scars that are evident even today.

Moreover, just as toxic waste must be marked clearly to warn off future civilizations, the ideological battlefields of the Cold War were embedded with markers — literal and metaphorical. Nations were left with monuments, museums, and memorials, along with political and cultural scars that serve as reminders of the deep fissures created by this global struggle. These markers are warnings, in a sense, designed to communicate across generations and epochs the dangers of a too-rigid adherence to a single ideology, especially one that many felt had the potential to mutate into a tyrannical or dystopian regime.

Looking into the future, the metaphor of burying communism like toxic waste carries a profound caution: it speaks to the need for vigilance and memory. Just as hazardous materials might one day resurface with dangerous consequences if not properly contained and remembered, ideological threats presumed buried could re-emerge if the lessons of history are forgotten. Thus, the containment strategy extends beyond the immediate tactical responses of military or economic policies; it implies a long-term commitment to education, to cultural understanding, and to the maintenance of historical consciousness.

This understanding of containment and its representation as a strategy against a disease or toxic threat also prompts critical reflection on the nature of ideological conflicts. It compels us to question how societies interpret political theories and their accompanying risks, and how these interpretations shape international actions and policies. The analogy to disease or toxic waste, while powerful, is also laden with the potential for exacerbating conflicts, dehumanizing opponents, and justifying extreme measures in the name of security and stability.

In sum, the containment of communism as if it were a contagious disease or toxic waste illustrates the intense fears and dramatic actions characterizing much of the 20th century’s international relations. The approach has left indelible marks on the global landscape, both in the physical and psychological realms, and its legacy continues to influence how political ideologies are perceived and managed. As we move forward, it is crucial for successive civilizations to understand this historical context, to decode the markers left behind, and to approach the future with both caution and wisdom, aware of the lessons taught by the past but also open to the possibilities of reconciliation and mutual understanding.

Image symbolizing the containment strategy against communism during the Cold War.